WHAT REMAINS, WHAT EMERGES

Laetitia Heisler transforms risk, memory, and the body into layered analogue visions — feminist rituals of seeing that reveal what endures, and what quietly emerges beyond visibility.

November 9, 2025

INTERVIEW

PHOTOGRAPHY Laetitia Heisler

INTERVIEW Melanie Meggs

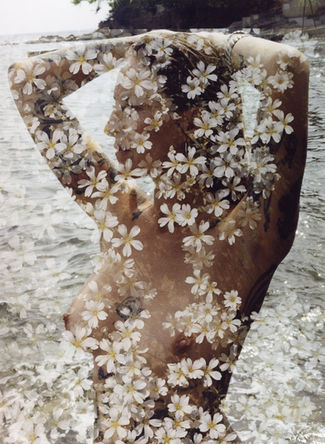

Double exposure has always carried a tension between accident and intention, between the technical error of overlapping frames and the creative act of constructing layered realities. In the analogue practice of French German visual artist Laetitia Heisler, this tension becomes the very site of inquiry. Working with RA-4 color printing, she reclaims the material instability of the medium as both aesthetic strategy and conceptual foundation. Her photographs exist not as fixed records but as mutable encounters, where body, landscape, and memory interlace to form images that hover between representation and apparition.

What distinguishes Laetitia’s work is the refusal of resolution. By reloading rolls of film, exposing scenes twice over, and submitting the negative to a process of reinvention in the darkroom, she generates visual spaces where presence and absence are no longer opposed but entangled. What emerges is not simply a double but a third presence, that hovers between representation and abstraction. In these compositions, photography shifts from the evidentiary to the performative, aligning itself more closely with ritual and self-portraiture.

Her work is profoundly autobiographical yet resists confession. It is shaped by Laetitia’s interest in the invisible: trauma, desire, menstrual cycles, psychic thresholds, and the body as a living archive. Here, the analogue darkroom functions not only as a site of technical manipulation but as a psychic chamber where shame and silence are reconfigured into visibility. The RA-4 color print becomes less a reproduction than a residue of performance — each manual intervention, distortion, and gesture embedded in the surface of the image.

To engage with Laetitia’s photographs is to enter a state of oscillation: between clarity and blur, intimacy and estrangement, recognition and disorientation. They recall the Pictorialism tradition in their embrace of softness and atmosphere, yet they remain insistently contemporary in their politics of feminist self-imaging and their emphasis on process over product. At once fragile and resistant, these works ask us to reconsider what it means to look, to remember, and to inhabit an image. We begin our conversation with Laetitia Heisler — asking what drives her devotion to analogue experimentation, how she approaches the risks and revelations of process, and what it means to transform the personal into shared visual experience.

“My practice and my inner life constantly shape one another, but what matters to me just as much is how this devotion reveals another way of relating to time. The darkroom demands slowness, patience, and attentiveness - qualities that are increasingly rare in a fast, efficiency-driven world. Many of my works are self-portraits, so enlarging an image often feels like allowing hidden layers to come into visibility. But beyond the personal, the process itself speaks of a different rhythm of existence, one that values pause, silence, and depth. My daily rhythms naturally mirror this: I gravitate toward the darkroom when I feel the need for solitude and when I want to step out of linear productivity, into a space where time stretches, bends, and transforms with the image.”

IN CONVERSATION WITH

LAETITIA HEISLER

TPL: Your practice is deeply founded in experimentation. What does risk mean to you in the analogue darkroom? Can you recall a moment when failure led to an unexpected breakthrough in your work?

LAETITIA: Experimentation is at the core of my practice. With it comes failure, unpredictability, and sometimes even loss. In analogue photography, risk is not only about trying something new without following established rules, but also about accepting that what was once captured on the negative can completely disappear in the darkroom. It accepts losing the control. In some of my experiments, I use unconventional liquids during development, and sometimes this means ruining an entire roll of film. But this loss is part of the point - it challenges material attachment and destabilizes the idea of photography as something fixed or permanent. Failure, repetition, and even destruction become part of the process. For one print, I might use dozens of sheets of paper - not to reach perfection, but to test limits, to see what happens when control slips away. In this sense, the darkroom is less a place of mastery than of negotiation, where the unexpected is allowed to intervene. When I teach analogue double-exposure workshops, I encourage participants to value the one image that works, but equally to pay attention to the many that fail. Each “mistake” opens another possibility. What matters is not the preservation of an image as an object, but the experience of process, of time, and of transformation.

TPL: You speak of the darkroom as both sanctuary and laboratory. How do you balance intuition with technical precision when working with film and RA-4 prints? Do you find that one — intuition or precision — dominates at particular stages of your process?

LAETITIA: My relationship with the darkroom began with learning the fundamentals. For black-and-white, I trained with Kira Enss at Butz Lab in Hamburg, and I was introduced to RA-4 printing at Stills in Edinburgh with Caroline Douglas. Once I had the technical foundations, I began to deliberately break them. I experiment with the process intuitively, relying on my five senses, often introducing gestures or movements that destabilize precision. For me, precision is never absent. It forms the structure, the framework. One cannot break rules without knowing them. But intuition grows within that framework when I get to know the image after having made a few prints of it. Then, the intuition grows increasingly, and I can completely let go by playing with the enlarger and filters, shifting the image or even bringing physical movement into the process. In this sense, the darkroom becomes both sanctuary and laboratory: a space where discipline and unpredictability constantly negotiate with one another.

TPL: Many artists working today are drawn to digital possibilities, yet you remain committed to analogue processes. What does analogue photography offer you that digital cannot? Do you see this commitment as an act of resistance in itself?

LAETITIA: I am not against digital tools, I may use them for video or other projects, but I remain deeply committed to analogue processes, mostly because they bring me joy. For me, making art should also carry a sense of play. Screens and social media often make me feel stressed, so analogue photography offers a counterbalance: a material, embodied practice. A real hug cannot be replaced by a lovely message on WhatsApp; in the same way, the physical experience of analogue work cannot be replaced by digital photography. To me, they are both completely different practices. Each having their pros and cons. In the darkroom, all the senses are engaged. My eyes are absorbed by the light produced by the enlarger, my nose is filled with the smell of chemistry, my hands navigate in complete darkness, my ears catch every small sound, even taste is connected to the air I breathe. This sensorial immersion does something to the mind - it grounds. It is comparable to being in a forest, where you are surrounded by air, smells, colors, sounds. I feel that analogue photography brings an anchoring quality, something material and direct, which is increasingly missing in our screen-driven lives. Today it is easy to feel disconnected from our immediate environment; I think that analogue photography is a way of restoring balance between the virtual and the material and that is why so many young people are going back to it.

TPL: The negative in your work is not an endpoint but a starting point. How do you understand the negative as a living material? Do you ever return to the same negative multiple times, and if so, how does each iteration evolve?

LAETITIA: In my practice, the negative is not a sacred object that needs to be enlarged according to conventional codes. For me, the negative is a medium, a point of departure to create images beyond the negative. Each time I return to the same negative - because I often do - something new can emerge. Printing becomes less about reproducing what was captured on film and more about opening possibilities. For me, this reflects the way reality itself operates. Reality is not a single, universal truth but a layered, shifting field - something that cannot be fully pinned down. By working the same negative again and again, with different tones, gestures, and movements, I want to make visible that multiplicity. The negative is alive because it carries within its infinite potential versions, just as reality is never one-dimensional but always in flux. This way, a single image may exist in different variations within the same edition — for example, print 1/7 might differ from print 2/7, even though they originate from the same negative.

TPL: Your self-portraits are performative and serve primarily as a way to externalize your subconscious and move beyond the psychological dissociation you have experienced. How do you navigate the boundary between self-exposure and self-protection? Are there aspects of your life or body you intentionally keep outside of your work?

LAETITIA: If there were things I intentionally kept outside my work, I certainly wouldn’t announce them. What matters to me in self-portraiture is not self-exposure for its own sake, but rather the act of questioning the viewer. For instance, in my series Ce que je ne veux pas dire, composed entirely of self-portraits, I use mirror passe-partouts to underline that what the viewer sees of me is ultimately a reflection of themselves and at the same time, the mirror serves as a form of protection, a way to shield parts of me while redirecting the gaze back onto the spectator. I resonate deeply with Francesca Woodman’s statement, “You cannot see me from where I see myself” (Francesca Woodman, 1958–1981). Of course, self-portraiture also serves me personally, but what it generates within me remains private. By showing these works, I am less concerned with revealing myself than with evoking what the human psyche so often endures in silence: fragmentation, vulnerability, multiplicity. It is, in fact, a claim for authenticity, for daring to truly look at ourselves rather than remaining in sterile relations. What interests me in self-portrait is not confession but resonance: creating images that become a mirror for collective inner experiences.

To me, art is about opening a space where we might ask how we are really doing, what remains hidden, and how those hidden aspects might be acknowledged.

TPL: Your images engage with trauma, desire, menstrual cycles, shame, and silence — subjects often erased from visual culture. What does it mean for you to make them visible through photography? Has working with these themes changed how you relate to your own body?

LAETITIA: Engaging with these themes has inevitably reshaped the way I relate to my own body and experiences. Take menstruation, for instance: like many menstruating people, I have endured both physical and psychological pain around it. But since menstrual blood has become a medium in my practice, whether through double exposures or by immersing negatives in it for 24 hours before development, my perception has shifted. I now anticipate my cycle not only as a physical event, but as an opportunity for my artistic practice. It transforms something often silenced or stigmatized into material for expression. Imagine if everybody would see menstrual blood as an opportunity! Making such subjects visible is not about provocation; it’s about dismantling taboos and expanding what we allow ourselves to see. Photography, for me, becomes a tool to re-inscribe these embodied experiences into visual culture, where they have long been erased. This process does not only alter my relationship to my own body but also asks viewers to confront aspects of their humanity often kept in the shadows: vulnerability, shame, cycles, desires. It is an invitation to acknowledge that these dimensions exist, to engage with them rather than turning away. And if some viewers feel discomfort when confronted with images addressing menstruation or trauma, then perhaps that discomfort itself should be questioned - why does it arise, and what does it reveal about the structures that shape our collective gaze?

TPL: You’ve mentioned affinities with early pictorialism. How do you reconcile that tradition’s romantic atmosphere with your more contemporary, political concerns? Are there specific Pictorialism photographers whose work resonates with you today?

LAETITIA: What draws me to early pictorialism is not so much its stylistic nostalgia, but its insistence on photography as an expressive, interpretive medium rather than a neutral reproduction of reality. Like the Pictorialists, I am interested in how an image can evoke emotion, atmosphere, or even ambiguity, rather than simply documenting the visible. Photographers such as Robert Demachy or René Le Bègue, with their emphasis on material interventions, remind me that the photographic image has always been open to manipulation, to being shaped as much by the hand as by the lens. Anne Brigman also resonates strongly with me: her use of the female body in dialogue with nature feels like an early feminist gesture, embedding subjectivity and lived experience directly into the image. Other figures also inspire me, not strictly pictorialism but adjacent, like Claude Cahun or Francesca Woodman. For me, these references are less about emulating a style than about situating myself within a history of artists who used photography as a space for transformation where process, emotion, and vulnerability outweigh clarity or control.

TPL: Your work asks viewers to reconsider what it means to look and to inhabit an image. What do you hope stays with someone after encountering your photographs? Do you think of your photographs as conversations that continue long after they leave the darkroom?

LAETITIA: What I hope lingers after someone encounters my work is not so much a fixed image, but a shift in perception, a question that stays with them. My photographs are less about offering answers than about creating space for introspection. If they provoke viewers to look inward, to reconsider how they see themselves and the world around them, then the work has fulfilled its role. I do think of photographs as conversations, but not in a didactic way. They are open-ended exchanges that unfold over time, sometimes resurfacing in unexpected moments. The darkroom may be where the image begins, but it only comes alive once it is carried into someone’s inner landscape, where it can continue to resonate, disturb, or even transform.

TPL: Photography has long been tied to evidence and truth. How do you see your practice challenging these conventions, particularly as a feminist intervention? Do you feel your photographs argue for a new kind of truth — one that is fluid, embodied, and multiple?

LAETITIA: My work, especially through multiple exposures, seeks to challenge the conditioning we inherit around the visible by layering, fragmenting, and reconfiguring it. I work only with tangible elements from my immediate surroundings - objects, textures, organic materials - to emphasize that what we perceive as “real” is always filtered through perspective, always multiple. In this sense, my practice resonates with Alexandra David-Néel, who explored what lies beyond appearances. She once wrote: “Truth learned from others is worthless. Only the truth we discover ourselves counts, only it is effective.” This does not mean rejecting facts or science but rather acknowledging that truth becomes transformative only when it is experienced directly. For me, the darkroom is precisely such a site: a place where the visible can be encountered in its instability, through experimentation and the senses. Even a single negative can unfold into endless variations. Working through sight, touch, smell, even sound, is what allows me to connect more deeply to the material world around me. This is also why I integrate menstrual blood into my work - whether by photographing it or incorporating it into the chemistry. It is both a way of entering into real contact with my body, through all senses, and a radical feminist gesture of reclaiming what has so often been silenced or erased from visual culture. In this way, photography becomes not about fixing one singular reality on an image, but about the process and about revealing that reality is embodied, fluid, and always uniquely experienced by each observer.

TPL: As you look toward the future of your artistic practice, what types of projects are you currently considering, and how do you envision these endeavors evolving over the next 3 to 5 years? Are there specific themes or issues you feel compelled to explore more deeply, and how do you see your style or approach transforming as you continue to grow as an artist?

LAETITIA: At the moment, I am pursuing several projects that continue to expand the relationship between body, psyche, and image. One ongoing research focuses on menstrual blood in photography, not only as a subject but as a material in itself. Alongside this, I am developing a large-scale installation composed of around 350 instant photographs taken over five years, exploring dissociation and the complexities of mental reaction to trauma.

I am also framing my series Ce que je ne veux pas dire, a body of double exposed self-portraits printed in the darkroom and presented with mirrored passe-partouts. For me, the mirror reframes the self-portrait as a relational image: the viewer is confronted with their own reflection. It shifts the vision of the self-portrait - although I appear in the image, it cannot be reduced to knowing me. What the viewer ultimately sees is filtered through their own eyes, their own experience.

In parallel to my darkroom practice, I am beginning to integrate sculptural work into my practice, extending my exploration of materiality beyond the photographic print. These new directions allow me to deepen questions of embodiment, vulnerability, and the multiplicity of realities. Over the next years, I see my practice evolving toward immersive forms, where image, object, and viewer coexist in spaces that do not simply present a work, but create an experience. My aim is to engage the spectator in a way that challenges both perception and intimacy, making it evident that the work is not complete without their presence.

TPL: When you’re not behind the camera or in the darkroom, what fun adventures or creative pursuits would we find Laetitia diving into?

LAETITIA: I’ve always been immersed in art in one form or another. Before photography, I was a dancer and later a musician, playing in a band for several years in my youth. Music still matters deeply to me - especially underground scenes. It keeps me connected to raw energy. When I do self-portraits, I always listen to John Lennon or Brian Jonestown Massacre. At the same time, I read, write, and draw a lot. Also, psychology fascinates me. I even enjoy staying in therapy as a way of continuing to explore the human psyche. Eastern philosophies, particularly from India, have also deeply influenced the way I live and work. I’ve been there to study meditation, ayurveda and know I am learning to speak Hindi. And of course, being on the road, walking endlessly through forests or wandering cities is something that makes me feel very alive. I also like to dive underwater, looking at fishes. Those underwater explorations, just like walking or traveling, are part of the adventures that feed my imagination.

In speaking with Laetitia Heisler, it becomes clear that her practice is not only about photography, but about the ways we inhabit time, body, and image. Through analogue experimentation she transforms risk into revelation, failure into possibility, and silence into visibility. Her darkroom is less a place where memory and material converge to create images that resist finality yet invite deep reflection.

What remains is Laetitia’s devotion to the unseen: to those psychic and embodied realities often hidden, stigmatized, or overlooked. By bringing menstrual cycles, trauma, and vulnerability into visual culture, she reclaims analogue photography as a feminist space of resistance and resonance. Her photographs are not answers but invitations, opening the possibility of seeing — and feeling — differently.

As Laetitia continues to expand her work into sculptural and immersive forms, her practice asks us to reconsider the photograph not as an endpoint but as an ongoing conversation between artist, image, and viewer. It is in this space of exchange, fragile yet profound, that her work finds its power — what remains, and what emerges.